Blog

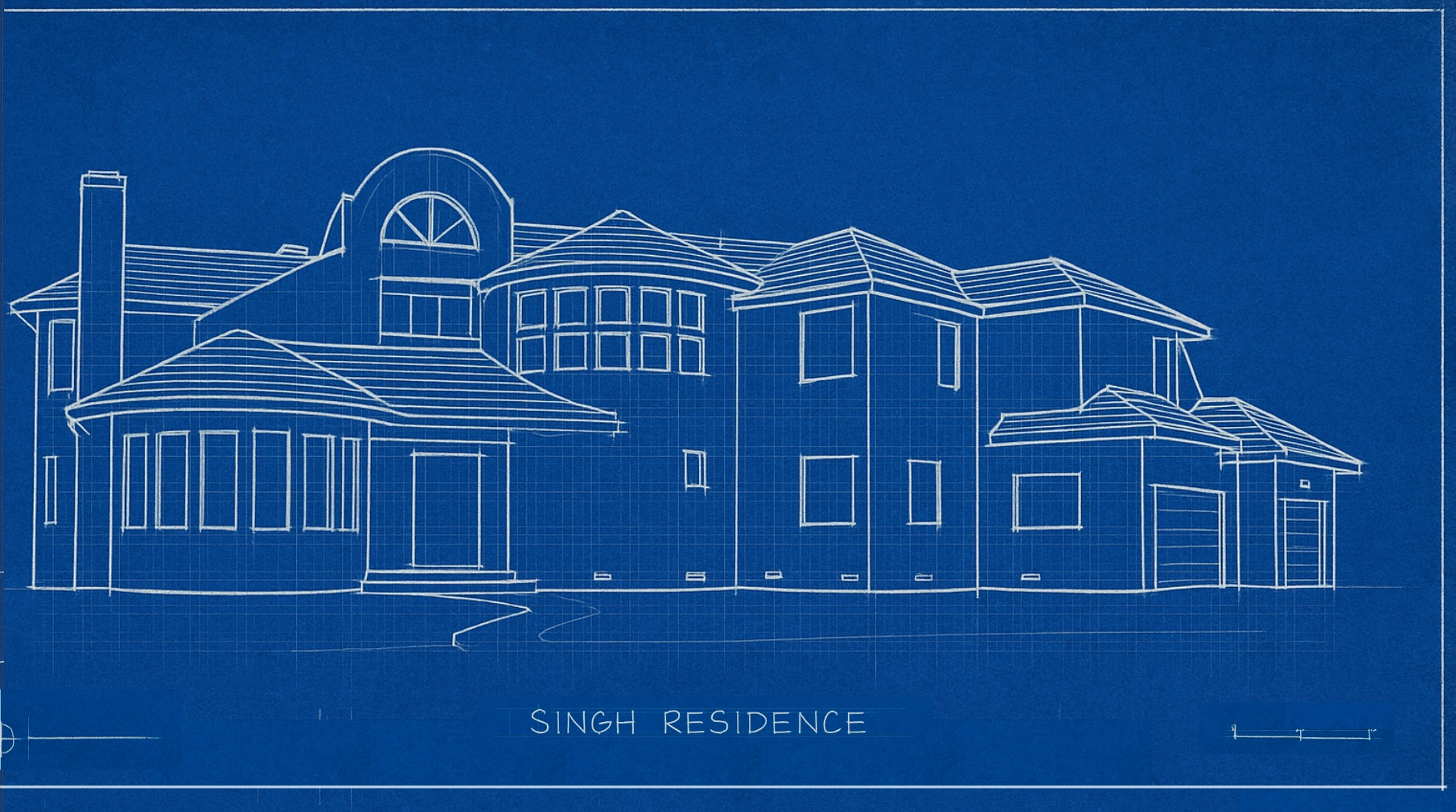

One of the first architects I ever worked with was named James Miller. We designed mansions in the hills around Silicon Valley.

Decades later, I found myself reading Living Systems Theory by another James Miller — James Grier Miller — a 1,102-page PDF I had managed to dig up online.

It felt like life was sending me the same message twice.

Coming from architecture, it all made instant sense: the world as nested structures, flows, exchanges, patterns within patterns.

It felt like discovering a deeper truth.

But I didn’t yet see the deeper illusion hiding inside it.

I still believed I was a separate mind looking at a system, rather than a participant shaped by it.

I thought there were “these systems” and then there was me — the observer, the analyst, the one who might someday help fix them.

It took years to see how deeply I had absorbed a story that made this separation seem natural.

Systems thinking reveals the hidden architecture of behavior.

Patterns underneath events.

Structures underneath outcomes.

Loops underneath habits.

It invites us to see beyond blame and personality, to notice how relationships shape everything.

For someone raised in a culture of individualism, this was liberating.

It loosened the belief that problems come from “bad people.”

It pointed instead to something more honest:

Most struggles come from the flows we’re swimming in, not the individuals inside them.

But even this clarity carries a subtle danger.

Once you start seeing relationships, a seductive logic emerges:

If we map the system well enough,

we can understand it well enough,

and if we understand it well enough,

we can fix it.

It feels objective, rational, empowered.

It feels like stepping into mastery.

But mastery requires distance —

and distance is the first lie individualism teaches us.

We imagine we can stand outside the system because we imagine we are separate from it.

As if our own fears, hopes, instincts, and adaptations aren’t themselves expressions of the very system we are trying to change.

Individualism taught us that we have a relationship to life.

It did not teach us that we are a relationship within life.

So we kept drawing diagrams as if we were outside looking in.

In architecture, I learned to design clean lines and elegant structures — but real homes are never the drawings. They shift with heat, settle with soil, breathe with the seasons, and reshape themselves through the people who inhabit them.

I didn’t see it then, but the same mistake I made with buildings was the mistake I made with systems:

I confused the diagram with the living thing.

No matter how elegant, a diagram is still a story we project onto something living.

It cannot feel the difference between trust and compliance, or sense fear rising in a room.

Nor can it know what it means to belong.

A diagram captures structure.

But structure is not what gives a system life.

Life is responsiveness — sensation — continuous movement toward balance.

A diagram cannot adapt.

And adaptation, not structure, is what makes the system alive.

For years, I looked at “the systems” as external structures or machines: things to study, diagnose, and redesign from the outside.

This was my deepest misunderstanding.

There is no place outside the system,

no vantage point untouched by the forces,

no observer who is not simultaneously a participant.

But individualism tells us otherwise.

Individualism tells us we are self-contained.

That our actions originate from “within.”

That our success and failures are personal.

It blinds us to the reality that everything we think, feel, or choose happens inside a living system that is self-producing, shaping us even as we try to shape it.

Individualism didn’t just distort our politics or our organizations.

It distorted our perception of reality itself.

It made us believe we aren’t the system.

This is the turning point.

There aren’t many systems.

There is only one system: Life.

Every other “system” — social, political, economic, organizational — is a symbolic layer, a human attempt to carve the wholeness of life into understandable parts.

But those parts are not separate.

Cells are not separate from bodies.

People are not separate from communities.

Communities are not separate from ecosystems.

Ecosystems are not separate from the planet.

Planets are not separate from the stars that give them life.

And none of us — not one — is separate from Life.

We do not “interact with” life.

We are life.

A process inside a process, a movement inside a larger movement, a pattern inside a pattern we did not create but continuously co-creating.

Systems thinking helped me see the patterns,

but not immediately my place within them.

The illusion of independence is powerful.

Everywhere now — in leadership books, in organizational design, regeneration work — we point to mycelium, forests, murmuration.

Look how life organizes itself.

Let’s make our systems work like life.

It’s a beautiful instinct — maybe the closest we get to remembering what we’ve forgotten.

But here is the quiet disconnect inside this trend:

Our systems don’t need to be like life.

Copying life remains a separation.

Imitation keeps life “over there” and us “over here,” hoping we can borrow its wisdom without returning to our place inside it.

We can draw mycelium-inspired org charts, swarm-based governance models — but none of those are alive.

Life is not a pattern to emulate.

It is a process to participate in.

We don’t need to design better diagrams.

We need systems that express the living forces at their roots.

We need to return our systems to the conditions of life.

Through the Life Lens, systems thinking becomes something much humbler:

A symbolic tool trying to remember a biological truth.

A story pointing back to a reality older than any story:

Life is relationship.

We are not separate from the world.

Feelings are adaptations.

Belonging is not optional.

Interdependence is not a philosophy —

it is the condition of existence.

Systems thinking is not the answer.

It is an invitation to remember what we once knew without diagrams:

We are not separate parts.

We are expressions of one living system.

One Life — in many forms.

Story created the illusion of separation.

Systems thinking helped reveal the illusion.

But only life — seen, lived, relational — can dissolve it.

This perspective echoes insights found across several fields: from Maturana and Varela’s view of life as self-producing, to Gregory and Nora Bateson’s reminders that the illusion of separateness is the root of systemic error, to David Bohm’s insistence that fragmentation is a product of thought — our story about the world — not reality.

Fritjof Capra pointed to life as a web of interdependence, and many Indigenous traditions have long held that humans are not observers of life but participants within it.

And James Grier Miller mapped life as nested flows across every scale.

These perspectives touch part of the picture and build what becomes clear through the Life Lens:

Life is the one system,

we are inseparable from it,

and systems thinking is a symbolic tool trying to remember how life lives.

Looking back now, those early architectural drawings feel like metaphors for the story I was living inside — tidy, controlled, separated from life.

But life is nothing like those drawings.

Life shifts.

Life adapts.

Life co-creates itself through relationship.

And the moment we stop treating our social systems as blueprints and start treating them as living structures, our stories can return to the one system we never left: Life.

Most of us have a moment when the map gave us clarity

but not connection.

A moment when the pattern made sense

but still acted from separation.

A moment where the diagram was accurate

but the relationship wasn’t alive.

These moments reveal the gap between story and life.

So here is the real question at the heart of “system thinking”:

What shifts when you stop trying to understand the system

and start recognizing that you are it?